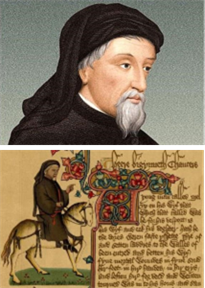

Робочий аркуш (a worksheet): "Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer"

THE CANTERBURY TALES by GEOFFREY CHAUCER

|

|

|

![]()

|

ABOUT THE MAIN STORY

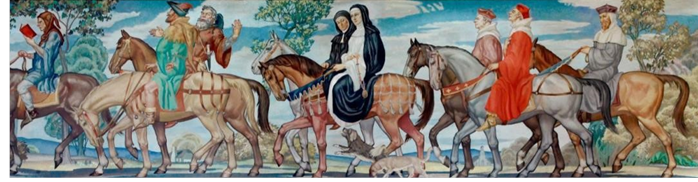

The framing story of The Canterbury Tales is quite simple. A group of about 30 pilgrims meet at the Tabard Inn in a London suburb, and agree to enter a storytelling contest as they travel on horseback to the sacred place of the martyr Thomas Becket, in Canterbury, Kent. The pilgrims are introduced by vivid brief sketches in The General Prologue. Among the 24 pilgrims’ tales there are inserted short dramatic scenes of lively talk, usually involving the host and some of the pilgrims. 24 tales must have been the full plan of the book: the return journey from Canterbury is not related, and some of the pilgrims have no stories. Use of pilgrimage as a framing device permitted Chaucer to bring together different people. We meet the three dominant groups that made up medieval society in England: the fe udal group, the church group and the city group. The storytelling competition also enabled the presentation of various literary genres: country romance, immodest fabliau, saint’s life, allegorical tale, medieval sermon, beast fable, fairy tales, alchemical account, legends, and also mixtures of these genres. The Canterbury Tales are written in rhymed heroic couplets, each line containing five stresses with regular alternation known as iambic pentameter, the most popular English poetic line, perhaps brought into English by Chaucer. In reading original Chaucer verse one must remember that the final ‘e’, which is silent in Modern English, could be pronounced at any time to provide a needed unstressed syllable.

|

|

CHARACTERS [pilgrims]: Cleric, Franklin, Friar, Host or Innkeeper, Knight, Man of Law, Merchant, Miller, Monk, Nun, Pardoner, Parson, Plowman, Prioress, Reeve, Scholarly Clerk, Summoner, Squire, Wife of Bath, Yeoman etc. STRUCTURE:

The Canterbury Tales consist of the General Prologue, The Knight’s Tale, The Miller’s Tale, The Reeve’s Tale, The Cook’s Tale, The Man of Law’s Tale, The Wife of Bath’s Tale, The Friar’s Tale, The Summoner’s Tale, The Clerk’s Tale, The Merchant’s Tale, The Squire’s Tale, The Franklin’s Tale, The Second Nun’s Tale, The Canon’s Yeoman’s tale, The Physician’s Tale, The Pardoner’s Tale, The Shipman’s Tale, The Prioress’s Tale, The Tale of Sir Thopas, The Tale of Melibeus (in prose), The Monk’s Tale, The Nun’s Priest’s Tale, The Manciple’s Tale, and The Parson’s Tale (in prose), and ends with “Chaucer’s Retraction”. Not all the tales are complete; several contain their own prologues or epilogues. |

|

ABOUT THE PARDONER’S TALE The cynical Pardoner explains in a witty Prologue that he sells indulgences ― ecclesiastical pardons of sins ― and admits that he preaches against avarice although he practices it himself. His tale related how three drunken revelers set out to destroy Death after one of their friends had died. An old man tells them that Death can be found under a particular oak tree in a grove, but when they arrive at the tree, they discover only a pile of gold florins. Two of men plot to kill the third so as to have more of the treasure for themselves.

However, after they killed their friend, they drink some wine that he had poisoned earlier, and they die too. The Pardoner concludes his tale by speaking in florid rhetoric against the vices of gluttony, gambling, and blasphemy ― adding at the end that he will be more than happy to secure divine forgiveness for his listeners, for a price.

|

FOCUS ON VOCABULARY:

FOCUS ON VOCABULARY:

cynical: contemptuously distrustful of human nature and motives avarice: excessive or insatiable desire for wealth or gain: greediness, cupidity rhetoric: the art of speaking or writing effectively gluttony: excess in eating or drinking

gambling: the practice of risking money or other stakes in a game or bet blasphemy: the act of insulting or showing contempt or lack of reverence for God

|

THE PARDONER’S TALE [by Geoffrey Chaucer]a story from The Canterbu ry Tales

It’s of three Who long before the morning service bellrioters I have to tell Were sitting in a tavern for a drink. And as they sat, they heard the hand-bell clink Before a coffin going to the grave; One of them called the little tavern-knave And said “Go and find out at once ― look spry! ― Whose corpse is in that coffin passing by; And see you get the name correctly too.”

“Sir,” said the boy, “no need, I promise you; Two hours before you came here I was told. He was a friend of yours in days of old, And suddenly, last night, the man was slain, Upon his bench, face up, dead drunk again.

There came a privy thief, they call him Death, Who kills us all round here […] The publican joined in with, “By Saint Mary, What the child says is right; you’d best be wary.” […] The rioter said, “Is he so fierce to meet?

I’ll search for him, by Jesus, street by street. God’s blessed bones! I’ll register a vow! Here, chaps! The three of us together now, Hold up your hands, like me, and we’ll be brothers In this affair and each defend the others,

And we will kill this Many and grisly were the oaths they swore,traitor Death, I say!” […] Tearing Christ’s blessed body to a shred; “If we can only catch him, Death is dead!” When they had gone not fully half a mile,

Just as they were about to cross a stile, They came upon a very poor old man Who humbly greeted them and thus began, “God look to you, my lords, and give you quiet!” To which the proudest of these men of riot

Gave back the answer, “What, old fool? Give place! Why are you all wrapped up except your face? Why live so long? Isn’t it time to die?”The old, old fellow looked him in the eye And said, “Because I never yet have found, Though I have walked to India, searching round Village and city on my pilgrimage, One who would change his youth to have my age.” […] “I heard you mention, just a moment gone, A certain traitor Death who singles out |

|

And kills the fine young fellows hereabout. And you’re his spy, by God! You wait a bit, Say where he is or you shall pay for it […]” “Well, sirs,” he said “if it be tour design To find out Death, turn up this crooked way

Towards that grove, I left him there today. […] You see that oak? He won’t be far to find. And God protect you that redeemed mankind, Aye, and amend you!” Thus that ancient man. At once the three young rioters began

To run, and reached the tree, and there they found A pile of golden florins on the ground, New-coined, eight bushels of them as they thought. No longer was it Death those fellows sought […] The wickedest spoke first after a while.

“Brothers,” he said, “you listen to what I say. I’m pretty sharp although I joke away. It’s clear that Fortune has bestowed this treasure To let us live in jollity and pleasure. This morning was to be our lucky day?”

“If one could only get the gold away, But certainly it can’t be done by day. People would call us robbers ― a strong gang, So our own property would make us hang. No, we must bring this treasure back by night

Some prudent way, and keep it out of sight. And so as a solution I propose We draw for lots and see the way it goes, The one who draws the longest, lucky man, Shall run to town as quickly as he can

To fetch us bread and wine ― but keep things dark While two remain in hiding here to mark Our heap of treasure. If there’s no delay, When night comes down we’ll carry it away.” […] It fell upon the youngest of them all,

And off he ran at once towards the town. As soon as he had gone the first sat down And thus began a parley with the other. “You know that you can trust me as a brother; Now let me tell you where your profit lies;

You know our friend has gone to get supplies And here’s a lot of gold that is to be Divided equally amongst us three. Nevertheless, if I could shape things thus So that we shared it out ― the two of us ―

Wouldn’t you take it as a friendly turn?” “But how?” the other said with some concern, “Trust me,” the other said, “you needn’t doubt […]

|

|

My word. I won’t betray you, I’ll be true.” “Well,” said his friend, “you see that we are two,

And two are twice as powerful as one. Now look; when he comes back, get up in fun To have a wrestle; then, as you attack, I’ll up and put my dagger through his back While you and he are struggling, as in game;

Then draw your dagger too and do the same. Then all this money will be ours to spend, Divided equally of course, dear friend.” […]

The youngest, as he ran towards the town, Kept running over, rolling up and down

Within his heart the beauty of those bright New florins, saying, “Lord, to think I might Have all that treasure to myself alone! Could there be anyone beneath the throne Of God so happy as I then should be?”

And so the Fiend, our common enemy, Was given power to put it in his thought That there was always poison to be bought, And that with poison he could kill his friends. […] And on he ran, he had no thoughts to tarry,

Came to the town, found an apothecary And said, “Sell me some poison if you will, I have a lot of rats I want to kill.” […] This cursed fellow grabbed into his hand The box of poison and away he ran

Into a neighboring street, and found a man Who lent him three large bottles. He withdrew And deftly poured the poison into two. He kept the third one clean, as well he might, For his own drink, meaning to walk all night

Stacking the gold and carrying it away. And when this rioter, this devil’s clay, Had filled his bottles up with wine, all three, Back to rejoin his comrades sauntered he. […] They fell on him and slew him, two to one.

***

Then said the first of them when this was done, “Now for a drink. Sit down and let’s be merry, For later on there’ll be the corpse to bury.” And, as it happened, reaching for a sup, He took a bottle full of poison up

And drank; and his companion, nothing loth, Drank from it also, and they perished both. […] Thus these two murderers received their due, So did the treacherous young poisoner too. |

|

TASKS to the material: 1. What language did Geoffrey Chaucer use for writing his poetry? 2. Read the texts about the author and the main plot and answer the questions: a) What interesting facts about Chaucer’s life do you know? b) What different occupations did he undertake? c) d) What literary genres are to be found in How was Chaucer praised by later writers and readers?The Canterbury Tales ? e) What are three groups of characters can we single out? Who are their representatives?

3. Read The Pardoner’s Tale and find synonyms for the following: mutineer, wicked, sensible, talk, murdered, regained, skillfully, dead body, traitorous 4. Guess the word by its definition: a) a person who steals things b) a person who betrays another person, or a common cause c) gold coins of Medieval Florence (Italy), also current in England d) owners’ possession |

5. Translate these collocations: by Jesus, a crooked way, I’m pretty sharp, a friendly turn, devil’s clay 6. Fill the gaps with the words from T4: a) So our own … would make us hang. b) There came a privy …, they call him Death. c) A pile of golden … on the ground. d) And we will kill this … Death.

7. Finish the sentences about the story: a) The three rioters sat in tavern and … b) They reached the tree and … c) On drawing their lots the youngest one … d) They fell on him …

8. Write your own story about human greed and treachery in a personal essay [200 words].

|

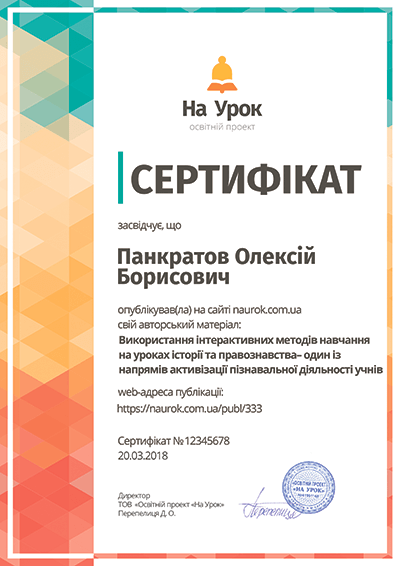

про публікацію авторської розробки

Додати розробку