Презентация :"J. R. R. Tolkien" часть 3

Презентация :"J. R. R. Tolkien" часть3

Linguistic career. Both Tolkien's academic career and his literary production are inseparable from his love of language and philology. He specialized in English philology at university and in 1915 graduated with Old Norse as special subject. He worked for the Oxford English Dictionaryfrom 1918 and is credited with having worked on a number of words starting with the letter W, including walrus, over which he struggled mightily. In 1920, he became Reader in English Language at the University of Leeds, where he claimed credit for raising the number of students of linguistics from five to twenty. He gave courses in Old English heroic verse, history of English, various Old English and Middle English texts, Old and Middle English philology, introductory Germanic philology, Gothic, Old Icelandic, and Medieval Welsh. When in 1925, aged thirty-three, Tolkien applied for the Rawlinson and Bosworth Professorship of Anglo-Saxon at Pembroke College, Oxford, he boasted that his students of Germanic philology in Leeds had even formed a "Viking Club".[He also had a certain, if imperfect, knowledge of Finnish.[Privately, Tolkien was attracted to "things of racial and linguistic significance", and in his 1955 lecture English and Welsh, which is crucial to his understanding of race and language, he entertained notions of "inherent linguistic predilections", which he termed the "native language" as opposed to the "cradle-tongue" which a person first learns to speak. He considered the West Midlands dialect of Middle English to be his own "native language", and, as he wrote to W. H. Auden in 1955, "I am a West-midlander by blood (and took to early west-midland Middle English as a known tongue as soon as I set eyes on it)."[Tolkien learned Latin, French, and German from his mother, and while at school he learned Middle English, Old English, Finnish, Gothic, Greek, Italian, Old Norse, Spanish, Welsh, and Medieval Welsh. He was also familiar with Danish, Dutch, Lombardic, Norwegian, Russian, Serbian, Swedish and older forms of modern Germanic and Slavonic languages,[178][unreliable source?] revealing his deep linguistic knowledge, above all of the Germanic languages.

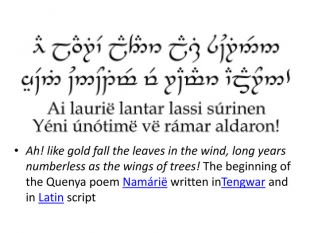

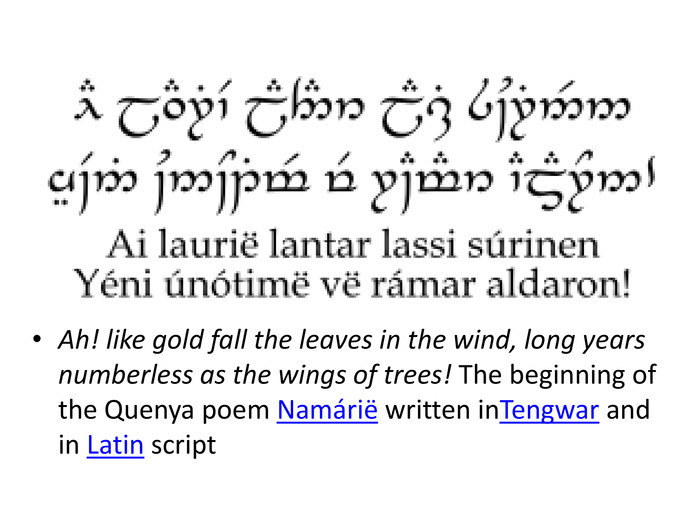

Language construction. Parallel to Tolkien's professional work as a philologist, and sometimes overshadowing this work, to the effect that his academic output remained rather thin, was his affection for constructing languages. The most developed of these are Quenya and Sindarin, the etymological connection between which formed the core of much of Tolkien's legendarium. Language and grammar for Tolkien was a matter of aesthetics andeuphony, and Quenya in particular was designed from "phonaesthetic" considerations; it was intended as an "Elvenlatin", and was phonologically based on Latin, with ingredients from Finnish, Welsh, English, and Greek.[146] A notable addition came in late 1945 with Adûnaic or Númenórean, a language of a "faintly Semitic flavour", connected with Tolkien's Atlantis legend, which by The Notion Club Papers ties directly into his ideas about the inability of language to be inherited, and via the "Second Age" and the story of Eärendil was grounded in the legendarium, thereby providing a link of Tolkien's 20th-century "real primary world" with the legendary past of his Middle-earth. Tolkien considered languages inseparable from the mythology associated with them, and he consequently took a dim view of auxiliary languages: in 1930 a congress of Esperantists were told as much by him, in his lecture A Secret Vice, "Your language construction will breed a mythology", but by 1956 he had concluded that "Volapük, Esperanto, Ido, Novial, &c, &c, are dead, far deader than ancient unused languages, because their authors never invented any Esperanto legends".[179]The popularity of Tolkien's books has had a small but lasting effect on the use of language in fantasy literature in particular, and even on mainstream dictionaries, which today commonly accept Tolkien's idiosyncratic spellings dwarves and dwarvish (alongside dwarfs and dwarfish), which had been little used since the mid-19th century and earlier. (In fact, according to Tolkien, had the Old English plural survived, it would have been dwarrows or dwerrows.) He also coined the termeucatastrophe, though it remains mainly used in connection with his own work.

Legacy. In a 1951 letter to Milton Waldman, Tolkien wrote about his intentions to create a "body of more or less connected legend", of which "[t]he cycles should be linked to a majestic whole, and yet leave scope for other minds and hands, wielding paint and music and drama". The hands and minds of many artists have indeed been inspired by Tolkien's legends. Personally known to him were Pauline Baynes (Tolkien's favourite illustrator of The Adventures of Tom Bombadil and Farmer Giles of Ham) and Donald Swann (who set the music to The Road Goes Ever On). Queen Margrethe II of Denmark created illustrations to The Lord of the Rings in the early 1970s. She sent them to Tolkien, who was struck by the similarity they bore in style to his own drawings. However, Tolkien was not fond of all the artistic representation of his works that were produced in his lifetime, and was sometimes harshly disapproving. In 1946, he rejected suggestions for illustrations by Horus Engels for the German edition of The Hobbit as "too. Disnified ... Bilbo with a dribbling nose, and Gandalf as a figure of vulgar fun rather than the Odinic wanderer that I think of". Tolkien was sceptical of the emerging Tolkien fandom in the United States, and in 1954 he returned proposals for the dust jackets of the American edition of The Lord of the Rings: Thank you for sending me the projected 'blurbs', which I return. The Americans are not as a rule at all amenable to criticism or correction; but I think their effort is so poor that I feel constrained to make some effort to improve it.[He had dismissed dramatic representations of fantasy in his essay "On Fairy-Stories", first presented in 1939: In human art Fantasy is a thing best left to words, to true literature. ... Drama is naturally hostile to Fantasy. Fantasy, even of the simplest kind, hardly ever succeeds in Drama, when that is presented as it should be, visibly and audibly acted.

Film adaptations. Tolkien scholar James Dunning coined the word Tollywood, a portmanteau derived from "Tolkien Hollywood," to describe attempts to create a cinematographic adaptation of the stories in Tolkien's legendarium aimed at generating good box office results, rather than at fidelity to the idea of the original. On receiving a screenplay for a proposed film adaptation of The Lord of the Rings by Morton Grady Zimmerman, Tolkien wrote: I would ask them to make an effort of imagination sufficient to understand the irritation (and on occasion the resentment) of an author, who finds, increasingly as he proceeds, his work treated as it would seem carelessly in general, in places recklessly, and with no evident signs of any appreciation of what it is all about. Tolkien went on to criticize the script scene by scene ("yet one more scene of screams and rather meaningless slashings"). He was not implacably opposed to the idea of a dramatic adaptation, however, and sold the film, stage and merchandise rights of The Hobbitand The Lord of the Rings to United Artists in 1968. United Artists never made a film, although director John Boorman was planning a live-action film in the early 1970s. In 1976 the rights were sold to Tolkien Enterprises, a division of the Saul Zaentz Company, and the first movie adaptation of The Lord of the Rings appeared in 1978, an animated rotoscoping film directed by Ralph Bakshi with screenplay by the fantasy writer Peter S. Beagle. It covered only the first half of the story of The Lord of the Rings.[186] In 1977 ananimated TV production of The Hobbit was made by Rankin-Bass, and in 1980 they produced an animated The Return of the King, which covered some of the portions of The Lord of the Rings that Bakshi was unable to complete. From 2001 to 2003, New Line Cinema released The Lord of the Rings as a trilogy of live-action films that were filmed in New Zealand and directed by Peter Jackson. The series was successful, performing extremely well commercially and winning numerous. Oscars. A series of three films based on The Hobbit, with Peter Jackson serving as executive producer, director, and co-writer, were released in 2012, 2013 and 2014. The first instalment, The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey was released in December 2012, and the second, The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug was released in December 2013. The last instalment The Hobbit: The Battle of the Five Armies was released in December 2014.[

Memorials. Posthumously named after Tolkien are the Tolkien Road in Eastbourne, East Sussex, and the asteroid 2675 Tolkien discovered in 1982. Tolkien Way in Stoke-on-Trent is named after Tolkien's eldest son, Fr. John Francis Tolkien, who was the priest in charge at the nearby Roman Catholic Church of Our Lady of the Angels and St. Peter in Chains. There is also a professorship in Tolkien's name at Oxford, the J. R. R. Tolkien Professor of English Literature and Language.[In the Dutch town of Geldrop, near Eindhoven, the streets of an entire new neighbourhood are named after Tolkien himself ("Laan van Tolkien") and some of the best-known characters from his books. A gaff-topsail schooner of Netherlands registry used for passenger cruises on the Baltic Sea and elsewhere in European waters was named J. R. Tolkien in 1998. In the Hall Green and Moseley areas of Birmingham there are a number of parks and walkways dedicated to J. R. R. Tolkien—most notably, the Millstream Way and Moseley Bog. Collectively the parks are known as the Shire Country Parks.[194] Every year at Sarehole Mill the Tolkien Weekend is held in memory of the author; the fiftieth anniversary of the release of The Lord of the Rings was commemorated in 2005. In the Silicon Valley towns of Saratoga and San Jose in California, there are two housing developments with street names drawn from Tolkien's works. About a dozen Tolkien-derived street names also appear scattered throughout the town of Lake Forest, California. At the University of California at Davis are "Baggins End Innovative Housing", an on-campus commune consisting of 14 polyurethane-insulated fibreglass domes, and an off-campus development known as "Village Homes", a planned community designed to be ecologically sustainable and whose street names are taken from The Lord of the Rings. At the University of California at Irvine is the "Middle Earth" housing community where each building is named after a place in The Hobbit or The Lord of the Rings. At the. University of California, Berkeley, the Berkeley Student Cooperative includes a vegetarian theme house known as Lothlorien, whose residents are known as "elves".[196]The genus Smaug, named after the dragon in The Hobbit, is a group of spiny southern African lizards, separated from the genus Cordylus in 2011 on the basis of a comprehensive molecular phylogeny of the Cordylidae. The type species is the giant girdled lizard, S. giganteus (formerly Cordylus giganteus).

The Columbia, Maryland, neighbourhood of Hobbit's Glen and its street names (including Rivendell Lane, Tooks Way, and Oakenshield Circle) come from Tolkien's works. There is also a Hobbit Restaurant in Ocean City, Maryland, and other locations throughout the world. Three mountains in the Cadwallader Range of British Columbia, Canada, have been named after Tolkien's characters. These are Mount Shadowfax, Mount Gandalf and Mount Aragorn. On 1 December 2012 it was announced in the New Zealand press that a bid was launched for the New Zealand Geographic Board to name a mountain peak near Milford Sound after Tolkien for historical and literary reasons and to mark Tolkien's 121st birthday. Since 2003 The Tolkien Society has organized Tolkien Reading Day, which takes place on 25 March in schools around the world. In Weston-super-Mare, Somerset, England there are a collection of roads in the 'Weston Village' named after locales of Middle Earth; Hobbiton Road, Bree Close, Arnor Close, Rivendell, Westmarch Way and Buckland Gre

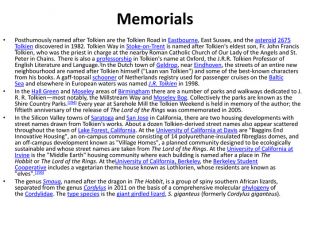

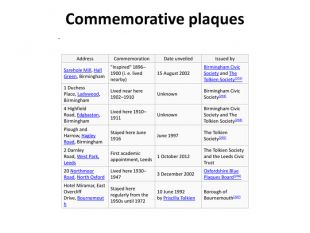

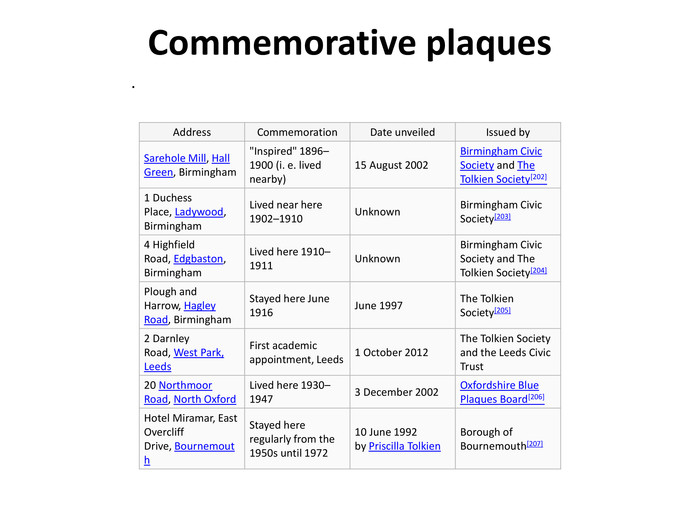

Commemorative plaques. Address. Commemoration. Date unveiled. Issued by. Sarehole Mill, Hall Green, Birmingham"Inspired" 1896–1900 (i. e. lived nearby)15 August 2002 Birmingham Civic Society and The Tolkien Society[202]1 Duchess Place, Ladywood, Birmingham. Lived near here 1902–1910 Unknown. Birmingham Civic Society[203]4 Highfield Road, Edgbaston, Birmingham. Lived here 1910–1911 Unknown. Birmingham Civic Society and The Tolkien Society[204]Plough and Harrow, Hagley Road, Birmingham. Stayed here June 1916 June 1997 The Tolkien Society[205]2 Darnley Road, West Park, Leeds. First academic appointment, Leeds1 October 2012 The Tolkien Society and the Leeds Civic Trust20 Northmoor Road, North Oxford. Lived here 1930–19473 December 2002 Oxfordshire Blue Plaques Board[206]Hotel Miramar, East Overcliff Drive, Bournemouth. Stayed here regularly from the 1950s until 197210 June 1992 by Priscilla Tolkien. Borough of Bournemouth[207].

There are seven blue plaques in England that commemorate places associated with Tolkien: one in Oxford, one in Bournemouth, four in Birmingham and one in Leeds. One of the Birmingham plaques commemorates the inspiration provided by Sarehole Mill, near which he lived between the ages of four and eight, while two mark childhood homes up to the time he left to attend Oxford University and the other marks a hotel he stayed at before leaving for France during World War I. The plaque in West Park, Leeds, commemorates the five years Tolkien enjoyed at Leeds as Reader and then Professor of English Language at the University. The Oxford plaque commemorates the residence where Tolkien wrote The Hobbit and most of The Lord of the Rings.

про публікацію авторської розробки

Додати розробку