Презентация :"J. R. R. Tolkien" часть1

Презентация :"J. R. R. Tolkien" часть1

![Austen's works critique the novels of sensibility of the second half of the 18th century and are part of the transition to 19th-century realism.[4][C] Her plots, though fundamentally comic,[5] highlight the dependence of women on marriage to secure social standing and economic security.[6] Her works, though usually popular, were first published anonymously and brought her little personal fame and only a few positive reviews during her lifetime, but the publication in 1869 of her nephew's A Memoir of Jane Austen introduced her to a wider public, and by the 1940s she had become widely accepted in academia as a great English writer. The second half of the 20th century saw a proliferation of Austen scholarship and the emergence of a Janeite fan culture. Austen's works critique the novels of sensibility of the second half of the 18th century and are part of the transition to 19th-century realism.[4][C] Her plots, though fundamentally comic,[5] highlight the dependence of women on marriage to secure social standing and economic security.[6] Her works, though usually popular, were first published anonymously and brought her little personal fame and only a few positive reviews during her lifetime, but the publication in 1869 of her nephew's A Memoir of Jane Austen introduced her to a wider public, and by the 1940s she had become widely accepted in academia as a great English writer. The second half of the 20th century saw a proliferation of Austen scholarship and the emergence of a Janeite fan culture.](/uploads/files/518/717/686_images/4.jpg)

Jane Austen 16 December 1775 – 18 July 1817) was an English novelist whose works of romantic fiction, set among the landed gentry, earned her a place as one of the most widely read writers in. English literature. Her realism, biting irony and social commentary as well as her acclaimed plots have gained her historical importance among scholars and critics. Austen lived her entire life as part of a close-knit family located on the lower fringes of the English landed gentry. She was educated primarily by her father and older brothers as well as through her own reading. The steadfast support of her family was critical to her development as a professional writer. From her teenage years into her thirties she experimented with various literary forms, including an epistolary novel which she then abandoned, wrote and extensively revised three major novels and began a fourth. From 1811 until 1816, with the publication of Sense and Sensibility (1811), Pride and Prejudice (1813), Mansfield Park (1814) and. Emma (1815), she achieved success as a published writer. She wrote two additional novels, Northanger Abbey and Persuasion, both published posthumously in 1818, and began a third, which was eventually titled. Sanditon, but died before completing it.

Austen's works critique the novels of sensibility of the second half of the 18th century and are part of the transition to 19th-century realism.[4][C] Her plots, though fundamentally comic,[5] highlight the dependence of women on marriage to secure social standing and economic security.[6] Her works, though usually popular, were first published anonymously and brought her little personal fame and only a few positive reviews during her lifetime, but the publication in 1869 of her nephew's A Memoir of Jane Austen introduced her to a wider public, and by the 1940s she had become widely accepted in academia as a great English writer. The second half of the 20th century saw a proliferation of Austen scholarship and the emergence of a Janeite fan culture.

Life and career. Biographical information concerning Jane Austen is "famously scarce", according to one biographer. Only some personal and family letters remain (by one estimate only 160 out of Austen's 3,000 letters are extant),and her sister Cassandra (to whom most of the letters were originally addressed) burned "the greater part" of the ones she kept and censored those she did not destroy. Other letters were destroyed by the heirs of Admiral Francis Austen, Jane's brother. Most of the biographical material produced for fifty years after Austen's death was written by her relatives and reflects the family's biases in favour of "good quiet Aunt Jane". Scholars have unearthed little information since.

Family. Austen's parents, George Austen (1731–1805) and his wife Cassandra (1739–1827), were members of substantial gentry families. George was descended from a family of woollen manufacturers, which had risen through the professions to the lower ranks of the landed gentre Cassandra was a member of the prominent Leigh family. They married on 26 April 1764 at Walcot Church in Bath. From 1765 until 1801, that is, for much of Jane's life, George Austen served as the rector of the Anglican parishes at Steventon, Hampshire and a nearby village. From 1773 until 1796, he supplemented this income by farming and by teaching three or four boys at a time who boarded at his home. Austen's immediate family was large: six brothers — James (1765–1819), George (1766–1838), Edward (1768–1852), Henry Thomas (1771–1850), Francis William (Frank) (1774–1865), Charles John (1779–1852) — and one sister,Cassandra Elizabeth (Steventon, Hampshire, 9 January 1773 – 1845), who, like Jane, died unmarried. Cassandra was Austen's closest friend and confidante throughout her life. Of her brothers, Austen felt closest to Henry, who became a banker and, after his bank failed, an Anglican clergyman. Henry was also his sister's literary agent. His large circle of friends and acquaintances in London included bankers, merchants, publishers, painters, and actors: he provided Austen with a view of social worlds not normally visible from a small parish in rural Hampshire. George was sent to live with a local family at a young age because, as Austen biographer Le Faye describes it, he was "mentally abnormal and subject to fits". He may also have been deaf and mute. Charles and Frank served in the navy, both rising to the rank of admiral. Edward was adopted by his fourth cousin, Thomas Knight, inheriting Knight's estate and taking his name in 1812.

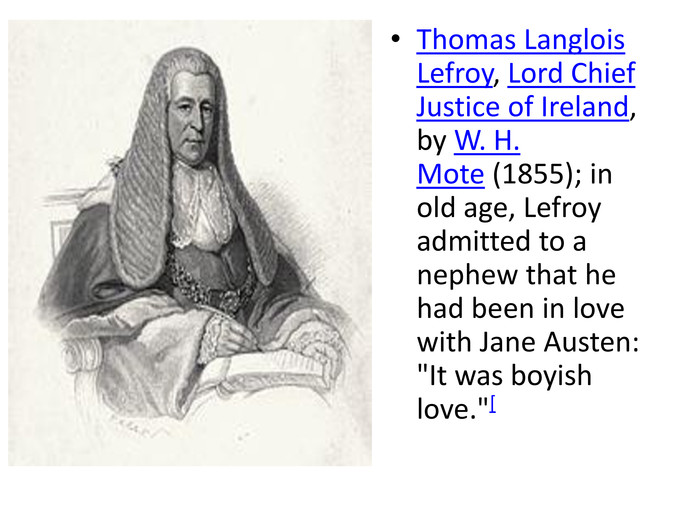

Early novels. After finishing Lady Susan, Austen attempted her first full-length novel — Elinor and Marianne. Her sister Cassandra later remembered that it was read to the family "before 1796" and was told through a series of letters. Without surviving original manuscripts, there is no way to know how much of the original draft survived in the novel published in 1811 as Sense and Sensibility. When Austen was twenty, Tom Lefroy, a nephew of neighbours, visited Steventon from December 1795 to January 1796. He had just finished a university degree and was moving to London to train as a barrister. Lefroy and Austen would have been introduced at a ball or other neighbourhood social gathering, and it is clear from Austen's letters to Cassandra that they spent considerable time together: "I am almost afraid to tell you how my Irish friend and I behaved. Imagine to yourself everything most profligate and shocking in the way of dancing and sitting down together." The Lefroy family intervened and sent him away at the end of January. Marriage was impractical, as both Lefroy and Austen must have known. Neither had any money, and he was dependent on a great-uncle in Ireland to finance his education and establish his legal career. If Tom Lefroy later visited Hampshire, he was carefully kept away from the Austens, and Jane Austen never saw him again.[52] The sentimental relationship between Jane and Tom is at the centre of the 2007 biographical film Becoming Jane. Austen began work on a second novel, First Impressions, in 1796. She completed the initial draft in August 1797 when she was only 21 (it later became Pride and Prejudice); as with all of her novels, Austen read the work aloud to her family as she was working on it and it became an "established favourite". At this time, her father made the first attempt to publish one of her novels. In November 1797, George Austen wrote to Thomas Cadell, an established publisher in London, to ask if he would consider publishing "a Manuscript Novel, comprised in three Vols. about the length of Miss Burney's Evelina" (First Impressions) at the author's financial risk. Cadell quickly returned Mr. Austen's letter, marked "Declined by Return of Post". Austen may not have known of her father's efforts. Following the completion of First Impressions, Austen returned to Elinor and Marianne and from November 1797 until mid-1798, revised it heavily; she eliminated the epistolary format in favour of third-person narration and produced something close to Sense and Sensibility. During the middle of 1798, after finishing revisions of Elinor and Marianne, Austen began writing a third novel with the working title Susan — later Northanger Abbey — a satire on the popular Gothic novel. Austen completed her work about a year later. In early 1803, Henry Austen offered Susan to Benjamin Crosby, a London publisher, who paid £10 for the copyright. Crosby promised early publication and went so far as to advertise the book publicly as being "in the press", but did nothing more. The manuscript remained in Crosby's hands, unpublished, until Austen repurchased the copyright from him in 1816.

Published author. During her time at Chawton, Jane Austen successfully published four novels, which were generally well received. Through her brother Henry, the publisher Thomas Egerton agreed to publish. Sense and Sensibility, which appeared in October 1811. Reviews were favourable and the novel became fashionable among opinion-makers; the edition sold out by mid-1813. Austen's earnings from Sense and Sensibility provided her with some financial and psychological independence. Egerton then published Pride and Prejudice, a revision of First Impressions, in January 1813. He advertised the book widely and it was an immediate success, garnering three favourable reviews and selling well. By October 1813, Egerton was able to begin selling a second edition. Mansfield Park was published by Egerton in May 1814. While Mansfield Park was ignored by reviewers, it was a great success with the public. All copies were sold within six months, and Austen's earnings on this novel were larger than for any of her other novels. Austen learned that the Prince Regent admired her novels and kept a set at each of his residences. In November 1815, the Prince Regent's librarian James Stanier Clarke invited Austen to visit the Prince's London residence and hinted Austen should dedicate the forthcoming Emma to the Prince. Though Austen disliked the Prince, she could scarcely refuse the request. She later wrote Plan of a Novel, according to hints from various quarters (fr), a satiric outline of the "perfect novel" based on the librarian's many suggestions for a future Austen novel. In mid-1815, Austen moved her work from Egerton to John Murray, a better known London publisher, who published Emma in December 1815 and a second edition of Mansfield Park in February 1816. Emma sold well but the new edition of Mansfield Park did not, and this failure offset most of the profits Austen earned on Emma. These were the last of Austen's novels to be published during her lifetime. The house in Winchester in which Jane Austen lived her last days and died. While Murray prepared Emma for publication, Austen began to write a new novel she titled The Elliots, later published as Persuasion. She completed her first draft in July 1816. In addition, shortly after the publication of Emma, Henry Austen repurchased the copyright for Susan from Crosby. Austen was forced to postpone publishing either of these completed novels by family financial troubles. Henry Austen's bank failed in March 1816, depriving him of all of his assets, leaving him deeply in debt and losing Edward, James, and Frank Austen large sums. Henry and Frank could no longer afford the contributions they had made to support their mother and sisters.

Reception. After Austen's death, Cassandra and Henry Austen arranged with Murray for the publication of Persuasion and Northanger Abbey as a set in December 1817. Henry Austen contributed a Biographical Note which for the first time identified his sister as the author of the novels. Tomalin describes it as "a loving and polished eulogy". Sales were good for a year—only 321 copies remained unsold at the end of 1818—and then declined. Murray disposed of the remaining copies in 1820, and Austen's novels remained out of print for twelve years. In 1832, publisher Richard Bentley purchased the remaining copyrights to all of Austen's novels and, beginning in either December 1832 or January 1833, published them in five illustrated volumes as part of his Standard Novels series. In October 1833, Bentley published the first collected edition of Austen's works. Since then, Austen's novels have been continuously in print.

Reception. Contemporary responses. Austen's works brought her little personal renown because they were published anonymously. Although her novels quickly became fashionable among opinion-makers, such as Princess Charlotte Augusta, daughter of the Prince Regent, they received only a few published reviews. Most of the reviews were short and on balance favourable, although superficial and cautious. They most often focused on the moral lessons of the novels. Sir Walter Scott, a leading novelist of the day, contributed one of them, anonymously. Using the review as a platform from which to defend the then-disreputable genre of the novel, he praised Austen's realism. The other important early review of Austen's works was attributed to Richard Whately in 1821. However, Whately denied having authored the review, which drew favourable comparisons between Austen and such acknowledged greats as Homer and Shakespeare, and praised the dramatic qualities of her narrative. Scott and Whately set the tone for almost all subsequent 19th-century Austen criticism.

Several important works paved the way for Austen's novels to become a focus of academic study. The first important milestone was a 1911 essay by Oxford Shakespearean scholar A. C. Bradley, which is "generally regarded as the starting-point for the serious academic approach to Jane Austen".[ In it, he established the groupings of Austen's "early" and "late" novels, which are still used by scholars today.[ The second was R. W. Chapman's 1923 edition of Austen's collected works. Not only was it the first scholarly edition of Austen's works, it was also the first scholarly edition of any English novelist. The Chapman text has remained the basis for all subsequent published editions of Austen's works.] With the publication in 1939 of Mary Lascelles's Jane Austen and Her Art, the academic study of Austen took hold. Lascelles's innovative work included an analysis of the books Jane Austen read and the effect of her reading on her work, an extended analysis of Austen's style, and her "narrative art". At the time, concern arose over the fact that academics were taking over Austen criticism and it was becoming increasingly esoteric — a debate that has continued to the beginning of the 21st century

про публікацію авторської розробки

Додати розробку