Доповідь "Стенфордський тюремний експеримент професора Філіппа Дж. Зімбардо"

PHILIP GEORGE ZIMBARDO

PHILIP GEORGE ZIMBARDO

… Our ability to selectively engage and disengage our moral standards… helps explain how people can be barbarically cruel in one moment and compassionate the next…

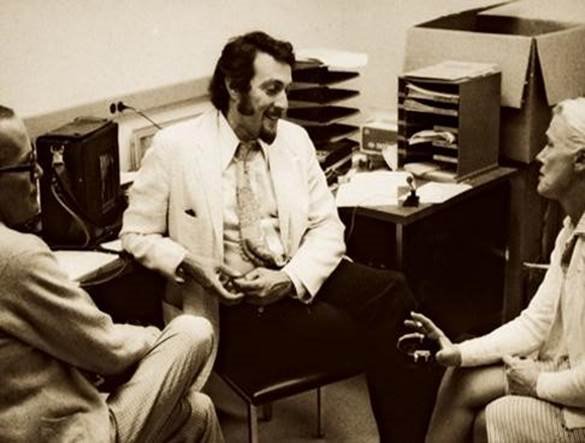

Zimbardo was born in New York City on March 23, 1933, to a family of Italian immigrants from Sicily. Early in life he experienced discrimination and prejudice, growing up poor on welfare and being Italian. He was often mistaken for other races and ethnicities such as Jewish, Puerto Rican or black. Zimbardo has said these experiences early in life triggered his curiosity about people's behavior, and later influenced his research in school.

Zimbardo was born in New York City on March 23, 1933, to a family of Italian immigrants from Sicily. Early in life he experienced discrimination and prejudice, growing up poor on welfare and being Italian. He was often mistaken for other races and ethnicities such as Jewish, Puerto Rican or black. Zimbardo has said these experiences early in life triggered his curiosity about people's behavior, and later influenced his research in school.

He completed his B.A. with a triple major in psychology, sociology, and anthropology from Brooklyn College in 1954, where he graduated summa cum laude. He completed his M.S. (1955) and Ph.D. (1959) in psychology from Yale University, where Neal E.

Miller was his advisor. While at Yale, he married fellow graduate student Rose Abdelnour; they had a son in 1962 and divorced in 1971.

He taught at Yale from 1959 to 1960. From 1960 to 1967, he was a professor of psychology at New York University College of Arts & Science. From 1967 to 1968, he taught at Columbia University. He joined the faculty at Stanford University in 1968.

Bibliography

• Influencing attitude and changing behavior: A basic introduction to relevant methodology, theory, and applications (Topics in social psychology), Addison Wesley, 1969

• The Cognitive Control of Motivation. Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman, 1969

• Stanford prison experiment: A simulation study of the psychology of imprisonment, Philip G. Zimbardo, Inc., 1972

• Influencing Attitudes and Changing Behavior. Reading, MA: Addison Wesley Publishing Co., 1969, ISBN 0-07-554809-7

• Canvassing for Peace: A Manual for Volunteers. Ann Arbor, MI: Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues, 1970, ISBN

• Influencing Attitudes and Changing Behavior (2nd ed.). Reading, MA: Addison Wesley., 1977, ISBN

• Psychology and You, with David Dempsey (1978).

• Shyness: What It Is, What to Do About It, Addison Wesley, 1990, ISBN 0-201-55018-0

• The Psychology of Attitude Change and Social Influence. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1991, ISBN 0-87722-852-3

• Psychology (3rd Edition), Reading, MA: Addison Wesley Publishing Co.,

1999, ISBN 0-321-03432-5

• The Shy Child : Overcoming and Preventing Shyness from Infancy to Adulthood, Malor Books, 1999, ISBN 1-883536-21-9

• Violence Workers: Police Torturers and Murderers Reconstruct Brazilian Atrocities. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2002, ISBN 0-520-23447-2

• Psychology - Core Concepts, 5/e, Allyn & Bacon Publishing, 2005, ISBN 0-205-47445-4

• Psychology And Life, 17/e, Allyn & Bacon Publishing, 2005, ISBN 0-205-41799-X

• The Lucifer Effect: Understanding How Good People Turn Evil, Random House, New York, 2007, ISBN 1-4000-6411-2

• The Time Paradox: The New Psychology of Time That Will Change Your Life, Simon & Schuster, New York, 2008, ISBN 1-4165-4198-5

• The Journey from the Bronx to Stanford to Abu Ghraib, pp. 85–104 in "Journeys in Social

Psychology: Looking Back to Inspire the Future", edited by Robert Levine, et al., CRC Press, 2008. ISBN 0-8058-6134-3

• Salvatore Cianciabella (prefazione di Philip Zimbardo, nota introduttiva di Liliana De Curtis).

Siamo uomini e caporali. Psicologia della dis-obbedienza. Franco Angeli,

2014. ISBN 978-88-204-9248-9. siamouominiecaporali.it

• Maschi in difficoltà, Zimbardo, Philip, Coulombe, Nikita D., Cianciabella, Salvatore (a cura di), FrancoAngeli Editore, 2017.

• Man (Dis)connected, Zimbardo, Philip, Coulombe, Nikita D., Rider/ Ebury Publishing, United Kingdom, 2015, ISBN 978-1846044847

• Man Interrupted: Why Young Men are Struggling & What We Can Do About It. Philip Zimbardo, Nikita Coulombe; Conari Press, 2016.

BACKGROUND

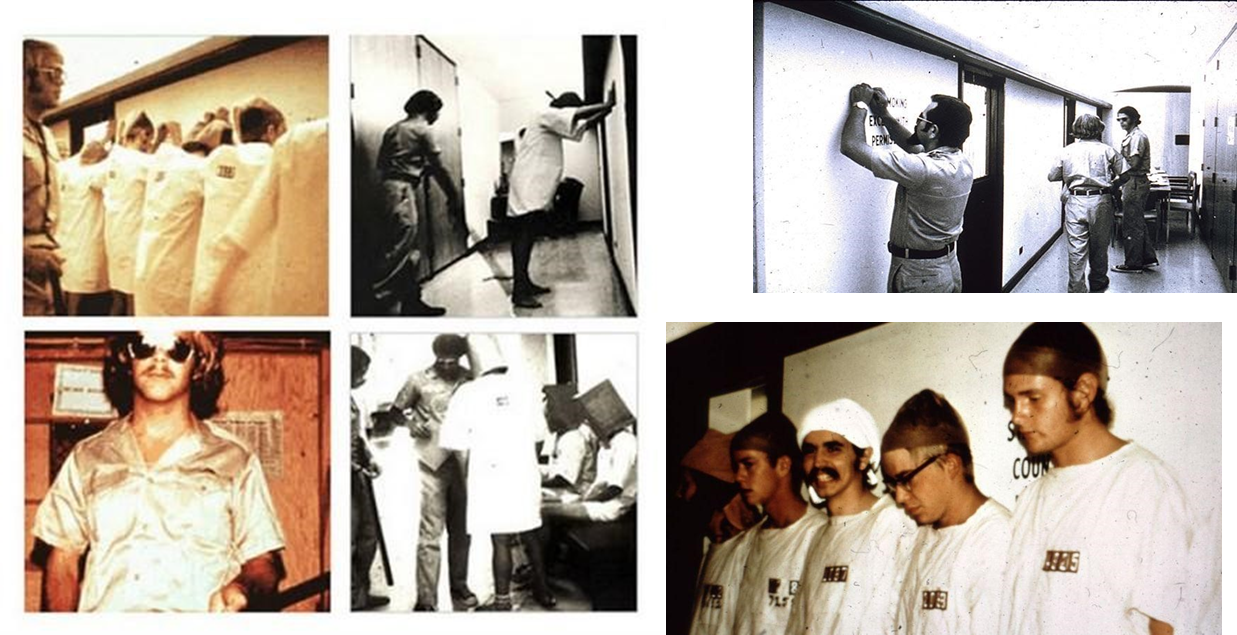

In 1971, Zimbardo accepted a tenured position as professor of psychology at Stanford University. With a government grant from the U.S. Office of Naval Research, he conducted the Stanford prison study in which male college students were selected (from an applicant pool of 75).

After a mental health screening, the remaining men were randomly assigned to be "prisoners" or "guards" in a mock prison located in the basement of the psychology building at Stanford. Prisoners were confined to a 6' x 9' cell with black steel-barred doors. The only furniture in each cell was a cot. Solitary confinement was a small unlit closet.

Zimbardo's goal for the Stanford Prison study was to assess the psychological effect on a (randomly assigned) student of becoming a prisoner or prison guard.

A 1997 article from the Stanford News Service described the experiment's goals in more detail:

Zimbardo's primary reason for conducting the experiment was to focus on the power of roles, rules, symbols, group identity and situational validation of behavior that generally would repulse ordinary individuals. "I had been conducting research for some years on deindividuation, vandalism and dehumanization that illustrated the ease with which ordinary people could be led to engage in anti-social acts by putting them in situations where they felt anonymous, or they could perceive of others in ways that made them less than human, as enemies or objects," Zimbardo told the Toronto symposium in the summer of 1996.

![]()

Experiment

Zimbardo himself took part in the study, playing the role of "prison superintendent" who could mediate disputes between guards and prisoners. He instructed guards to find ways to dominate the prisoners, not with physical violence, but with other tactics, verging on torture, such as sleep deprivation and punishment with solitary confinement. Later in the experiment, as some guards became more aggressive, taking away prisoners' cots (so that they had to sleep on the floor), and forcing them to use buckets kept in their cells as toilets, and then refusing permission to empty the buckets, neither the other guards nor Zimbardo himself intervened. Knowing that their actions were observed but not rebuked, guards considered that they had implicit approval for such actions.

In later interviews, several guards told interviewers that they knew what Zimbardo wanted to have happen, and they did their best to make that happen.

Less than two full days into the study, one inmate began suffering from depression, uncontrolled rage, crying and other mental dysfunctions. The prisoner was eventually released after screaming and acting in an unstable manner in front of the other inmates. This prisoner was replaced with one of the alternates.

|

Results

![]()

By the end of the study, the guards had won complete control over all of their prisoners and were using their authority to its greatest extent. One prisoner had even gone as far as to go on a hunger strike. When he refused to eat, the guards put him into solitary confinement for three hours (even though their own rules stated the limit that a prisoner could be in solitary confinement was only one hour). Instead of the other prisoners looking at this inmate as a hero and following along in his strike, they chanted together that he was a bad prisoner and a troublemaker. Prisoners and guards had rapidly adapted to their roles, stepping beyond the boundaries of what had been predicted and leading to dangerous and psychologically damaging situations. Zimbardo himself started to give in to the roles of the situation. He had to be shown the reality of the study by Christina Maslach, his girlfriend and future wife, who had just received her doctorate in psychology. Zimbardo reflects that the message from the study is that "situations can have a more powerful influence over our behaviour than most people appreciate, and few people recognize [that]."

![]()

At the end of the study, after all the prisoners had been released and the guards let go, everyone was brought back into the same room for evaluation and to be able to get their feelings out in the open towards one another. Ethical concerns surrounding the study often draw comparisons to the Milgram experiment, which was conducted in 1961 at Yale University by Stanley Milgram, Zimbardo's former high school friend.

![]()

More recently, Thibault Le Texier of the University of Nice has examined the archives of the experiment, including videos, recordings, and Zimbardo's handwritten notes, and argued that "The guards knew what results the experiment was supposed to produce ... Far from reacting spontaneously to this pathogenic social environment, the guards were given clear instructions for how to create it ... The experimenters intervened directly in the experiment, either to give precise instructions, to recall the purposes of the experiment, or to set a general direction ...In order to get their full participation, Zimbardo intended to make the guards believe that they were his research assistants.". Since his original publication in French, Le Texier's accusations have been taken up by science communicators in the United States. In his book Humankind - a hopeful history (2020) historian Rutger Bregman points out the charge that the whole experiment was faked and fraudulous; Bregman argued this experiment is often used as an example to show people easily succumb to evil behavior, but Zimbardo has been less than candid about the fact that he told the guards to act the way they did. More recently, an APA psychology article reviewed this work in detail and concluded that Zimbardo encouraged the guards to act the way they did, so rather than this behavior appearing on its own, it was generated by Zimbardo.

![]()

The Lucifer Effect

![]()

The Lucifer Effect was written in response to his findings in the Stanford Prison Experiment. Zimbardo believes that personality characteristics could play a role in how violent or submissive actions are manifested. In the book, Zimbardo says that humans cannot be defined as good or evil because we have the ability to act as both especially at the hand of the situation. Examples include the events that occurred at the Abu Ghraib Detention Center, in which the defense team—including Gary Myers—argued that it was not the prison guards and interrogators that were at fault for the physical and mental abuse of detainees but the Bush administration policies themselves. According to Zimbardo, "Good people can be induced, seduced, and initiated into behaving in evil ways. They can also be led to act in irrational, stupid, self-destructive, antisocial, and mindless ways when they are immersed in 'total situations' that impact human nature in ways that challenge our sense of the stability and consistency of individual personality, of character, and of morality."(Zimbardo, The Lucifer Effect, p. 211)

![]()

In The Journal of the American Medical Association,

|

There are seven social processes that grease "the slippery slope of evil": |

▪ Mindlessly taking the first small step ▪ Dehumanization of others ▪ De-individuation of self (anonymity) ▪ Diffusion of personal responsibility ▪ Blind obedience to authority ▪ Uncritical conformity to group norms ▪ Passive tolerance of evil through inaction or indifference |

![]()

The Banality of Evil: Life After the Stanford Prison Experiment

Philip Zimbardo's Stanford prison experiment: reviews, analysis, conclusions

Philip Zimbardo's Stanford prison experiment: reviews, analysis, conclusions

Stanford prison experiment

про публікацію авторської розробки

Додати розробку