Методичні рекомендації " Dictogloss as a new grammar technicque"

|

ЛНВК "ЗОШ І-ІІІ ст. № 22-ліцей" |

|

Dictogloss as a new grammar technique |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Created by Natalia Demchuk

|

Dictogloss as a new grammar technique / Н.І.Демчук - Луцьк: ЛНВК "ЗОШ І-ІІІ ст. № 22 – ліцей", 2015 - ст. 26

|

|

У даних методичних рекомендаціях розглядається метод диктоглосу, який поєднує в собі традиційні форми навчання та спільне навчання, а також його варіації та способи проведення. Він втілює кілька важливих принципів вивчення мови, такі як самостійність студентів, співпраця з учнями, зосередженість на змісті і само оцінюванні.

Рекомендовано до друку методичною радою ЛНВК "ЗОШ І-ІІІ ступенів № 22- ліцей". Протокол № 3 від 16 cічня 2015 р.

Content

- Introduction………………………………………………..3

- Dictogloss and current trends in second language education…………………………………………………..5

- Variations on dictogloss…………………………………………………11

- Dictogloss on practice…………………………………………………...19

- Conclusions………………………………………………23

- References………………………………………………..27

Introduction

Dictation has a long history in literacy education, particularly second language education. In the standard dictation procedure, the teacher reads a passage slowly and repeatedly. Students write exactly what the teacher says. Dictation in this traditional form has been criticized as a rote learning method in which students merely make a copy of the text the teacher reads without doing any thinking, thus producing a mechanical form of literacy. Ruth Wajnryb (1990) is credited with developing a new way to do dictation, known as dictogloss.

Dictogloss is often regarded as a multiple skills and systems activity. Learners practise listening, writing and speaking (by working in groups) and use vocabulary, grammar and discourse systems in order to complete the task.

Unlike traditional dictation, there is a gap between the listening and writing phases, giving learners time to think and discuss how best to express the ideas. The aim is not to reproduce the text word for word, but to convey the meaning and style of the text as closely as possible.

Dictogloss is a powerful way of focusing attention on precise meaning, as well as on correct use of grammar.

While there are many variations on dictogloss –we will be describing some of these later in this article -the basic format is as follows:

1.

The class engages in some discussion on the topic of the upcoming text. This topic is one on which students have some background knowledge and, hopefully, interest. The class may also discuss the text type of the text, e.g., narrative, procedure, or explanation, and the purpose, organizational structure, and language features of that text type.

2.

The teacher reads the text aloud once at normal speed as students listen but do not write. The text can be selected by teachers from newspapers, textbooks, etc., or teachers can write their own or modify an existing text. The text should be at or below students’ current overall proficiency level, although there may be some new vocabulary. It may even be a text that students have seen before. The length of the text depends on students’ proficiency level

3.

The teacher reads the text again at normal speed and students take notes.

Students are not trying to write down every word spoken; they could not even if they tried, because the teacher is reading at normal speed.

4.

Students work in groups of two-four to reconstruct the text in full sentences, not in point form (also known as bullet points). This reconstruction seeks to retain the meaning and form of the original text but is not a word-for-word copy of the text read by the teacher. Instead, students are working together to create a cohesive text with correct grammar and other features of the relevant text type, e.g., procedure, or rhetorical framework, e.g., cause and effect, that approximates the meaning of the original.

5.

Students, with the teacher’s help, identify similarities and differences in terms of meaning and form between their text reconstructions and the original, which is displayed on an overhead projector or shown to students in another way.

Dictogloss has been the subject of a number of studies and commentaries, which have, for the most part, supported use of the technique (Brown, 2001; Cheong, 1993; Kowal & Swain,1994, 1997; Lim, 2000; Lim & Jacobs, 2001a, b; Llewyn, 1989; Nabei, 1996; Storch, 1998;Swain, 1999; Swain & Lapkin, 1998; Swain & Miccoli, 1994). Among the reasons given for advocating the use of dictogloss are that students are encouraged to focus some of their attention on form and that all four language skills–listening (to the teacher read the text and to groupmates discuss the reconstruction), speaking (to groupmates during the reconstruction), reading (notes taken while listening to the teacher, the group’s reconstruction, and the original text), and writing the reconstruction)–are involved. Further potential benefits of the technique are discussed later in this paper.

Dictogloss has been the subject of a number of studies and commentaries, which have, for the most part, supported use of the technique (Brown, 2001; Cheong, 1993; Kowal & Swain,1994, 1997; Lim, 2000; Lim & Jacobs, 2001a, b; Llewyn, 1989; Nabei, 1996; Storch, 1998;Swain, 1999; Swain & Lapkin, 1998; Swain & Miccoli, 1994). Among the reasons given for advocating the use of dictogloss are that students are encouraged to focus some of their attention on form and that all four language skills–listening (to the teacher read the text and to groupmates discuss the reconstruction), speaking (to groupmates during the reconstruction), reading (notes taken while listening to the teacher, the group’s reconstruction, and the original text), and writing the reconstruction)–are involved. Further potential benefits of the technique are discussed later in this paper.

Dictogloss represents a major shift from traditional dictation. When implemented conscientiously, dictogloss embodies sound principles of language teaching which include learner autonomy, cooperation among learners, curricular integration, focus on meaning, diversity, thinking skills, alternative assessment, and teachers as co-learners. These principles flow from an overall paradigm shift that has occurred in second language education (Jacobs & Farrell, 2001).

In this section, we discuss each of these eight overlapping trends with reference to dictogloss. The Steps referred to below are the five steps in the standard dictogloss procedure described in the Introduction section above.

- Learner Autonomy.

Learner autonomy involves learners having some choice as to what and how of the curriculum and, at the same time, feeling responsible for and understanding their own learning and for the learning of classmates.

In dictogloss, as opposed to traditional dictation, students reconstruct the text on their own after the teacher has read it aloud to them just twice at normal speed (Steps 2 and 3), rather than the teacher reading the text slowly and repeatedly. Also, students need to help each other to develop a joint reconstruction of the text (Step 4), rather than depending on the teacher for all the information. Furthermore, Step 5 provides students with opportunities to see where they have done well and where they may need to improve. Swain (1999) believes that, “Students gain insights into their own linguistic shortcomings and develop strategies for solving them by working through them with a partner” (pp. 145). Ways to add other dimensions of learner autonomy to dictogloss are students:

- asking for a pause in the dictation;

- choosing the topics of the texts, selecting the texts themselves, and taking the teacher’s place to read the text;

- elaborating on the text;

- giving their opinions about the ideas in the text.

- Cooperation among Learners.

Traditional dictation was done as an individual activity. Dictogloss retains an individual element (Steps 2 and 3) in which students work alone to listen to and take notes on the text read by the teacher. In Step 4 of dictogloss, learners work together in groups of between two and four members. Additionally, in Step 5, they have the opportunity to discuss how well their group did and, perhaps, how they could function more effectively the next time.

- Curricular Integration.

From the perspective of language teachers, curricular integration involves combining the teaching of content, such as social studies or science, with the teaching of language, such as writing skills or grammar. As in traditional dictation, with dictogloss, curricular integration is easily achieved via the selection of texts. For instance, if the goal is to integrate language and mathematics in order to help students learn important mathematics vocabulary and grammar, language teachers (in consultation with mathematics teachers and, perhaps, students) can use a mathematics text for the dictogloss. The discussion prior to the readings of the text (Step 1) helps students recall and build their knowledge of the text’s topic. As Brown (2001, p. 2) points out, “Writing this information [what students know on the topic] on the chalk board allows the students to notice the wealth of information they have as a collective.” In addition to promoting integration between language education and other curricular areas, dictogloss, as noted earlier, also promotes integration within the language curriculum, as all four language skill –listening, speaking, reading, and writing - are utilized.

- Focus on Meaning.

In literacy education, the focus used to lie mostly on matters of form, such as grammar and spelling. In the current paradigm, while form still matters, the view is that language learning takes place best when the focus is mainly on ideas (Littlewood, 1981). Dictogloss seeks to combine a focus on meaning with a focus on form (Brown, 2001). As Swain (1999) puts it, “When students focus on form, they must be engaged in the act of ‘meaning-making’” (pp. 125-126).

- Diversity.

Perhaps it is appropriate that the term ‘diversity’ has a few different meanings. One of the meanings particularly relevant to dictogloss is that, due to 4 differences in background and in ways of learning (Gardner, 1999) different people will attend to different information. This is reflected in the variation in the notes that students take in Step 3. Working in a group in Step 4 allows learners to take advantage of this type of diversity. A second meaning of diversity suggests that different students will have different strengths (Cohen, 1998) which may lead them to play different roles in their group. For instance, those with larger vocabularies and greater content knowledge in the topic of the text can help with that part of the reconstruction, and those whose interpersonal skills are better developed may often help coordinate the group’s interaction.

There are a number of ways of using diversity to facilitate each student being a helper (the star) in their group, rather than always being the one receiving help from their more proficient partners. One, we can use a range of topics, striving in particular to read texts on topics which less proficient students know about. Two, students can create visuals to illustrate their text reconstructions. In this way, those students whose illustration skills are currently better than their literacy skills have a chance to shine.

- Thinking Skills.

The definition of literacy has been expanded beyond being able to read and write to also being able to think critically about what is read and about how to best frame what is written. The discussion that takes place during Step 4 of dictogloss provides learners with chances to use thinking skills as they challenge, defend, learn from, and elaborate on the ideas presented during collaboration on the reconstruction task. Thinking skills also come into play in Step 5 as students analyze their reconstructed text in relation to the original. We can challenge students’ skill at identifying main ideas by asking them to write summaries rather than text reconstructions and to elaborate on the texts read.

- Alternative Assessment.

Assessment measures insecond language education have been criticized for a focus on measuring language acquisition out of context, e.g., by testing proficiency via single words or isolated sentences rather than whole texts (Omaggio Hadley, 2001). In response to these criticisms, a range of more context-based alternative assessment procedures have been developed, including think aloud (Block, 1992), peer critique (Ghaith, 2002), portfolios (Pierce & O’Malley, 1992), and dialogue journals (Peyton, 1993).

Dictogloss offers a context-rich method of assessing how much students know about writing and about the topic of the text. The text reconstruction task provides learners with opportunities to display both their knowledge of the content of the text as well as of the organizational structure and language features of the text (Derewianka, 1990). As students discuss with each other during Steps 4 and 5, teachers can listen in and observe students’ thinking as they about a task. This real-time observation of learners’ thinking process offers greater insight than does looking at the product after they have finished. In this way, dictogloss supplies a process-based complement to traditional product-based modes of assessment. Furthermore, students are involved in self-assessment and peer assessment.

- Teachers as Co-learners.

The current view in education sees teachers not as all-knowing sages but instead as fellow learners who join with their students in the quest for knowledge. This knowledge can pertain specifically to teaching and learning, or it can be knowledge on any topic or sphere of activity. Dictogloss may be of use here in at least two ways. First, as mentioned in the last paragraph, we can observe students and apply what we learn from our observations in order to teach better.

Second, during Step 1, we can share with students our interest in the topic of the dictogloss text and some of what we have done and plan to do to learn more about it or to apply related ideas.

Second, during Step 1, we can share with students our interest in the topic of the dictogloss text and some of what we have done and plan to do to learn more about it or to apply related ideas.

Variation A: Dictogloss Negotiation

Variation A: Dictogloss Negotiation

In Dictogloss Negotiation, rather than group members discussing what they heard when the teacher has finished reading, students discuss after each section of text has been read. Sections can be one sentence long or longer, depending on the difficulty of the text relative to students’ proficiency level

- Students sit with a partner, desks face-to-face rather than side-by-side. This encourages discussion. After reading the text once while students listen, during the second reading, the teacher stops after each sentence or two, or paragraph. During this pause, students discuss but do not write what they think they heard. As with standard dictogloss, the students’ reconstruction should be faithful to the meaning and form of the original but does not employ the identical wording.

- One member of each pair writes the pair’s reconstruction of the text section. This role rotates with each section of the text.

- Students compare their reconstruction with the original as in Step 5 of the standard procedure.

Variation B: Student-Controlled Dictation

In Student-Controlled Dictation, students use the teacher as they would use a tape recorder. In other words, they can ask the teacher to stop, go back, i.e., rewind, and skip ahead, i.e., fast-forward. However, students bear in mind that the aim of dictogloss is the creation of an appropriate reconstruction, not a photocopy.

- After reading the text once at normal speed with students listening but not taking notes, the teacher reads the text again at natural speed and continues reading until the end if no student says “stop” even if it is clear that students are having difficulty. Students are responsible for saying “stop, please” when they cannot keep up and “please go back to (the last word or phrase they have written).” If students seem reluctant to exercise their power to stop us, we start reading very fast. We encourage students to be persistent; they can “rewind” the teacher as many times as necessary. The class might want to have a rule that each student can only say “please stop” one time. Without this rule, the same few students –almost invariably the highest level students -may completely control the pace. The lower proficiency students might be lost, but be too shy to speak. After each member of the class has controlled the teacher once, anyone can again control one time, until all have taken a turn. Once the class comprehends that everyone can and should control the teacher if they need help, this rule need not be followed absolutely.

- Partner conferencing (Step 4 in standard dictogloss) can be done for this variation as well. Student-Controlled Dictation can be a fun variation, because students enjoy explicitly controlling the teacher.

- Another way of increasing student control of dictation is to ask them to bring in texts to use for dictation or to nominate topics.

Variation C: Student - Student Dictation.

Rather than the teacher being the one to read the text, students take turns to read to each other. Student-Student Dictation works best after students have become familiar with the standard dictogloss procedure. This dictogloss variation involves key elements of cooperative learning, in particular equal participation from all group members, individual accountability (each member takes turns controlling the activity) and positive interdependence as group members explore meaning and correctness together.

- A text - probably a longer than usual one - is divided into four or five sections. Each student is given a different section. Thus, with a class of 32 students and a text divided into four sections, eight students would have the first section, eight the second, etc. Students each read the section they have been given and try to understand it. If the text is challenging, students with the same section can initially meet in groups of three or four to read and discuss the meaning.

- In their original groups, students take turns reading their section of the text as the teacher would for standard dictation while their groupmates take notes. Students work with their partners to reconstruct the text, with the students taking the role of silent observer when the section they read is being reconstructed.

- For the analysis, Step 5 of the standard procedure, each student plays the role of the teacher when the section they read is being discussed. Every group member eventually plays the role of teacher. Student-Student Dictation can also be done by students bringing in the own texts rather than using a text supplied by the teacher.

Variation D: Dictogloss Summaries

While in the standard dictogloss procedure students attempt to create a reconstruction of approximately the same length as the original, in Dictogloss Summaries, students focus only on the key ideas of the original text.

- Steps 1, 2, and 3 are the same as in standard dictogloss, although to encourage summarizing rather than using the words of the original text, the teacher might ask students not to take any notes.

- Students work with a partner to summarize the key points of the text. Here, as well as in other dictogloss variations, we can provide a visual cue (sketch, flow chart, photo, mind map) that represents some elements of the story. This aids comprehension and may help students structure their reconstruction. Additionally, students can create visuals to accompany their reconstructions, as another means to demonstrate comprehension and to promote unique reconstructions.

Variation E: Scrambled Sentence Dictogloss

Scrambled Sentences is a popular technique for teaching a number of language skills. Scrambled Sentences Dictogloss employs this technique to raise the difficulty level of dictogloss and to focus students’ attention on how texts fit together.

- The teacher jumbles the sentences of the text before reading it to students.

- When students reconstruct the text, they first have to recreate what they heard and then put it into a logical order.

- When analyzing students’ reconstructions, the class may decide that there is more than one possible correct order. This fits with the overall spirit of dictogloss, i.e., that there is no one correct way to achieve a communicative purpose, although there are certain conventions that should be understood and considered.

Variation F: Elaboration Dictogloss

In Elaboration Dictogloss, students go beyond what they hear to not just recreate a text but also to improve it. This dictogloss method may be preceded by a review of ways to elaborate, such as adding adjectives and adverbs, examples, facts, personal experiences, and causes and effects.

In Elaboration Dictogloss, students go beyond what they hear to not just recreate a text but also to improve it. This dictogloss method may be preceded by a review of ways to elaborate, such as adding adjectives and adverbs, examples, facts, personal experiences, and causes and effects.

After taking notes on the text read by the teacher, as in Step 3 of the standard procedure, students reconstruct the text. Then, they add elaborations. These can be factual, based on what students know about the topic of the text or research they do, or students can invent elaborations.

For instance, part of the text read by the teacher might be: Today, many students use bicycles.

Students could simply elaborate by adding a word or two:

Today, many Japanese college students use bicycles.

Or, a sentence or two could be added:

Today, many students use bicycles. This reduces air pollution and helps students stay fit. However, bicycle riding in a crowded city can be dangerous.

Variation G: Dictogloss Opinion

In Dictogloss Opinion, after students reconstruct the text, they give their opinion on the writers’ ideas. These opinions can be inserted at various points in the text or can be written at the end of the text. If student commentary is inserted throughout the text, it promotes a kind of dialogue with the original authors of the text.

Variation H : Picture Dictation

Dictation does not always have to involve writing sentences and paragraphs. Instead, students can do other activities based on what the teacher reads to them. For instance, they can complete a graphic organizer. Another possibility, described below, is to draw.

- The teacher finds or writes a description of a drawing. The description should include a great deal of detail. Relevant vocabulary and concepts can be reviewed in the discussion that occurs in Step 1 of the standard dictogloss procedure.

- Students listen to the description and do a drawing based on what they hear.

- Students compare drawings with their partners and make one composite drawing per pair.

- Students compare their drawing with the original.

- Alternatively, students can reconstruct the description text read by the teacher, as in standard dictogloss, and then do a drawing.

There are many posts and articles around the Internet covering the dictogloss application, so do go ahead and do some further exploration.

There are many posts and articles around the Internet covering the dictogloss application, so do go ahead and do some further exploration.

One in particular I liked was by David Dodgson and Ceri Jones. They have a great post on the topic which I highly recommend you check out.

Now I suggest reading some practice experience from David Dodson.

Phase 1 - Pre-task

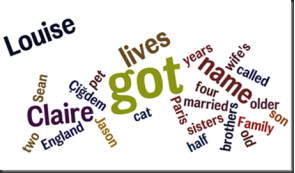

Anyway, onto my lesson. They had recently covered family in their main lessons so I decided to read them a short passage about my own family. As they had never done dictogloss before, I needed to offer them plenty of support so I utilised the pre-task phase to recap family words and get them thinking. I did this by displaying a word cloud made from my text, which you can see below:

I first asked them what family words and names they could see and then asked them to speculate in pairs about who these people might be. We then compared predictions, discussed which ones were more likely and put them on the board. The first task when listening to the text was to check which predictions were right. I supported the first reading with photos of my family so they could make a visual connection with the people I mentioned and I encouraged them to ask any questions they had (they were especially interested in my son and the cat!)

Here’s the text as I read it:

“I’ve got two sisters, Louise and Claire but I haven’t got any brothers. Louise lives in England but Claire lives in Pairs! I’m married. My wife’s name is Çiğdem and we’ve got a son. His name is Jason Demir and he’s four and a half years old. We’ve got a pet cat too. He’s called Sean.”

Phase 2 - Take note(s)

For the next phase, they needed to listen and take notes. As this was the first time they had tried dictogloss, I gave them a table to structure their note-taking (they were also unfamiliar with the concept of notes so it was useful for framing it), like this one:

|

Information |

Yes/no? How many? |

Extra information? |

|

Sisters? |

|

|

|

Brothers? |

|

|

|

Married? |

|

|

|

Children? |

|

|

|

Pets? |

|

|

They listened again and filled in the first column and then listened a couple more times to find extra information (names, ages, where they live etc.). Once they were happy they had enough notes, they compared their notes in pairs, filling any missing gaps and clarifying any clashing information. One thing that threw a few of them, for example, was when I said “We’ve got a pet cat too” with some of them thinking I meant I had two cats. The great thing was, most of the pairings were able to resolve this misunderstanding by themselves when they checked their notes together!

Phase 3 - Reconstructing & comparing

I then asked them to use their notes to re-write my text. That got a few puzzled looks at first but, with some prompting, they got the idea. I provided support by displaying the word cloud again as well as the photos, which I directed them to when they were struggling with spelling or the exact information needed. This phase of the lesson was completed fairly quickly so the pairs were then asked to read through their text again and check it. Next, I matched pairs together to make groups of four and had them compare their texts, looking for any differences (for both content and language).

The final phase entailed the class comparing their texts with the original as a final noticing activity. The act of comparing, first in small groups and then as a class, allowed them to see where they had made errors and I believe this is much more effective than me simply telling them. Many students, for example, corrected their peers when they had written ‘Louise live in England’, pointing out they should add -s to the verb. Through this collaborative comparison process, they were even able to reconstruct things they haven’t formally been taught yet like He’s called…

A good challenge

Of course, the lesson was not without its problems. Some students were disappointed when I revealed the original text and they saw they hadn’t got it 100% the same. I had to explain that there were several ways to say the same thing and the point was to make a good paragraph with the information I gave them, not something word-for-word the same.

On the whole, it went well (although one girl did, quite rightly, scold me for failing to include I love my family at the end of the text!) and I will be doing it again with slightly longer texts in the near future. In one class, we finished the lesson with a new word as I asked them what they thought of the lesson and whether they had found it easy or difficult. They wanted to say it wasn’t easy but wasn’t so difficult that they didn’t enjoy it. Challenging was the word they were looking for.

Conclusions

The dictogloss model offers several potential advantages over other models of teaching listening comprehension.

First, the dictogloss method is an effective way of combining individual and group activities. Students listen and take notes individually and then work together to reconstruct the texts. The reconstruction task gives students focus and a clear objective, which is a pre-condition for effective group work. Students are actively involved in the learning process and there are multiple opportunities for peer learning and peer teaching. After the teacher provides a framework for understanding the passage by explaining the background information, cooperative groups can develop more appropriate comparisons or examples that will assist learners with their comprehension (Thornton, 1999).

Second, the dictogloss procedure facilitates the development of the learners’ communicative competence. Students’ speaking time is significantly longer than in a traditional teacher-centered classroom. At the same time, the pressure to reconstruct the text within the time limit also means that students are more likely to use time effectively. Furthermore, unlike in a typical discussion class where students are presented with a list of topics or discussion questions and communication activities often have a simple question-and-answer format, in a dictogloss class, students’ interaction is much more natural. A collaborative reconstruction task gives learners the opportunities to practice and use all modes of language and to become engaged in authentic communication. There is more turn-taking and students are more likely to use confirmation and clarification strategies. The variety of interaction was found to be more productive in terms of language development than the actual linguistic forms used (Wills & Wills, 1996). As Long and Robinson (1998)point out, people learn languages best not by treating them as an object of study, but by experiencing them as a medium of communication.

Third, the reconstruction stage helps students try out their hypotheses and subsequently to identify their strengths and weaknesses. A reconstruction task encourages students to consider the input more closely. Noticing is known to be one of the crucial elements of the language learning process (Ellis, 1995). The reconstruction and correction stages help the students to compare input to their own representation of the text and to identify the possible gaps. It is through this process of cognitive comparison that new forms are incorporated, students’ language competence improves and students' interlanguage is restructured.

The dictogloss procedure also promotes learners’ autonomy. Students are expected to help each other recreate the text rather than depend on the teacher to provide the information. The analysis and correction stage enables the students to see where they have done well and where they need to improve. Students gain insights into their linguistic shortcomings and also develop strategies for solving the problems they have encountered.

Dictogloss also offers a unique blending of teaching listening comprehension and the assessment of students’ listening ability. Traditional tests formats such as true or false items, multiple choice or open-ended questions are often not sensitive enough to capture the specific problems that learners may have at different levels of the meaning comprehension process. They typically allow only a relatively small number of selected items to be tested (e.g. main ideas, lexical items, and so on) while the rest of the text remains uncovered. If we look at a test as a diagnostic tool, then more detailed information about learners’ understanding at different stages of the comprehension process is necessary. For the dictogloss task, learners need phonemic identification, lexical recognition, syntactic analysis and semantic interpretation. The reconstruction task offers an insight into the students’ performance at all stages of the speech perception process. With the checklist that follows both teachers and learners can verify whether or not learning is taking place, and can identify the parts of the text and specific words or structures that cause miscomprehension. Furthermore, the nature of the reconstruction task forces students to listen carefully to other students’ input, providing additional opportunities for listening practice.

The reconstruction task also promotes the acquisition of L2 vocabulary. Students need to recall the meaning and the written form of vocabulary items introduced at the preparation stage. In addition, by asking students to use new words to form complex sentences, teachers can direct the learners’ attention to collocations and usage restriction in the target language.

Another advantage of the dictogloss approach is that reconstruction tasks can raise students’ awareness of rhetorical patterns in the target language. Generic and rhetorical patterns are often culture specific (Kaplan, 1966). Reconstruction tasks facilitate students’ ability to understand and manipulate the patterns of textual organization and make them more sensitive to discourse markers and other cohesive ties in the language they are trying to acquire.

Finally, working in small groups reduces learners’ anxiety as they have to perform only in front of “a small audience.” This approach may be particularly suitable for those cultures in which students tend to be reticent and are not used to voicing their ideas in front of the whole class. In Japan, for example, students are often shy and group conscious. They feel insecure about their English ability and rarely volunteer their answers. They seldom initiate conversation, generally avoid bringing up new topics and rarely seek clarification (Burrows, 1996). When asked a direct question by a teacher, an individual student will often turn to her peers and seek advice before producing a response. Students feel more relaxed and confident when they share ideas that represent a group rather than themselves only. Group interaction is also important for the feedback stage. Peer feedback can either draw students' attention to gaps in their language knowledge or provide confirming feedback which consolidates that knowledge (Storch, 1998), while eliminating the students' fear that they will be “punished” for the mistakes they have made. In short, the dictogloss approach helps students put aside affective factors and therefore may be suited for collectivist countries such as Japan or Korea, where students' shyness is a common problem.

References

- Buck, G. (2001). Assessing Listening. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Jacobs, G. and Small, J. (2003). Combining dictogloss and cooperative learning to promote language learning. The

Reading Matrix 3 (1): 1-15.

- Swain, M. & Lapkin, S. (1998). Interaction and second language learning: Two adolescent French immersion students

working together. The Modern Language Journal, 82: 320-337.

- Wajnryb, R. (1990). Grammar dictation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- http://eslcarissa.blogspot.com/2012/09/5-fun-ways-to-use-dictagloss-in-efl.html

- http://www.readingmatrix.com/articles/jacobs_small/article.pdf

- http://authenticteaching.wordpress.com/2009/09/29/dictogloss/

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dictogloss

- http://www.davedodgson.com/2010/11/our-first-time-with-dictogloss.html

1

про публікацію авторської розробки

Додати розробку